This is the first in a series of articles examining potential future Systemic Dependency Risks. In conjunction with case studies of past events, they are meant to sketch out the potential scope and magnitude of Systemic Dependency Risk events, and hopefully provoke thought about vulnerability to this scenario, as well as other potential Systemic Dependency Risk scenarios with similar characteristics.

The universal, continuous availability of a GPS1 signal to provide a location’s relatively precise latitude and longitude is one of those modern miracles that we often take for granted. A device with a GPS receiver can determine its coordinates if it can receive signals from at least four GPS satellites and a straightforward geometric calculation.

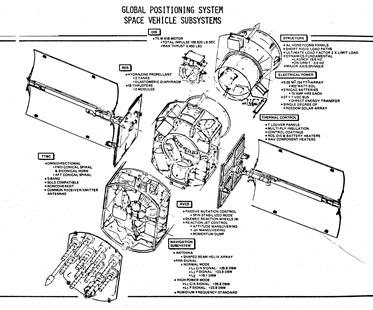

Complete global coverage is achieved with 24 orbiting satellites with 4 spaced evenly in each of 6 orbital planes approximately 20 thousand kilometers above the Earth. The satellites were originally deployed from 1978 to 1991, and have been periodically replaced with improved equipment and augmented with additional satellites. There are currently 31 operational satellites, of which 12 are second-generation design replacements launched between 1997 and 2009 (“Block IIR” and “Block IIRM”) that are all well beyond their original 10 year design life, 11 are second-generation design replacements launched between 2010 and 2016 (“Block IIF”) that are soon approaching the end of their original 12 or 15 year design lives, and 8 are third-generation design launched after 2018 (“Block III”) with 15 year design life. There are an additional 2 third-generation design replacements ready for launch soon, with 12 more in production or on order for launches from 2028 to 2032.

From science fiction to commonplace indispensable utility

At first, GPS was primarily for military purposes, and civilian use was deliberately degraded by adding a time-varying pseudorandom error to the signal such that position was only accurate to within about 50 meters. This “Selective Availability” feature was disabled in 2000.

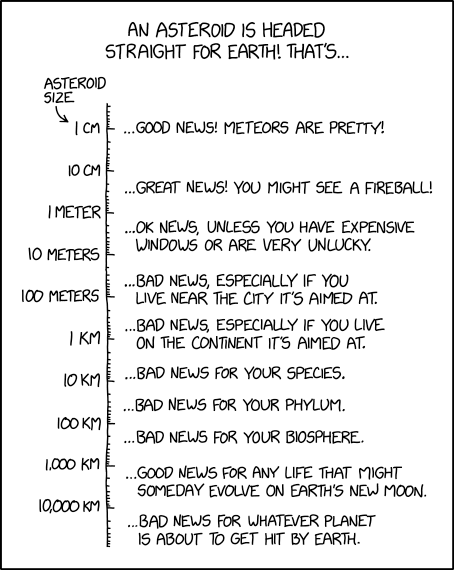

The early devices were huge:

Source: National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

To be fair, these early devices included the antenna, processor, battery, input pad and display. As technology improved, GPS receiver chips and antennae have become small – typically less than a couple of centimeters wide – and relatively cheap such that they can be included in many consumer and commercial devices that have their own power supplies and user interfaces.

Mobile phones began integrating GPS receivers in the early 2000s, most prominently with the iPhone 3G in 2008. Availability of GPS coordinates in mobile phones fueled an array of location-based app services, in particular navigation and driving directions, as well as rideshare, delivery, mobile ordering, etc. While these are now commonplace integrated with our daily lives, it’s important to remember that these capabilities and the business models that have grown around them are only around 20 years old.

A less obvious use of GPS arises from the synchronized universal time stamp contained in its signal, which is used to measure distance in the GPS receiver’s calculation of location. While individual devices and networks might have their own built-in clocks, these clocks will all develop slight differences over time. Clocks can be resynchronized using the free timestamp contained in the GPS signal, or other applications may use the GPS timestamp directly.

Synchronized time across networks is critical to coordinating operations in electrical grids and telecommunications. It’s particularly important for managing traffic and handoffs in cellular networks. It’s also key for time-stamping transactions in the financial sector.

As ubiquitous and fundamental as GPS availability has become, it does have some points of fragility in each of its key components: the satellites generating the signals, transmission of the signal through the atmosphere (especially the ionosphere), the end-users’ receivers, and the ground-based control system that monitors the satellites and adjusts their orbits and clocks.

We’ll first look at the potential impact of a GPS outage, and then outline some of the potential ways such an outage might occur.

What would happen if GPS went down?

Were GPS suddenly unavailable at a national or global scale for a protracted period, chaos would immediately erupt – perhaps similar to the CrowdStrike outage in terms of things unexpectedly not working and significant knock-on effects, but probably even more widespread.

Driving directions would be unavailable via mobile devices and many drivers would need to stop and make alternative navigation plans. In this day and age, how many people know how to find a map and read it so as to figure out directions on their own?

Airplanes in-flight at the time of the GPS outage may need to land immediately due to concerns about safe navigation and collision avoidance. Further air traffic would likely be grounded initially and then put on constrained schedules to ensure safe navigation using manual and visual methods.

Some ships in tricky areas to navigate might run aground, and traffic at busy ports would grind to a halt with container ships switching to manual navigation, and the location of dockside containers suddenly no longer precisely known. The situation might look somewhat like Maersk’s terminal shutdowns in the 2017 NotPetya cyberattack, but in every large modern port around the world rather than just 17 of the 86 operated by Maersk.

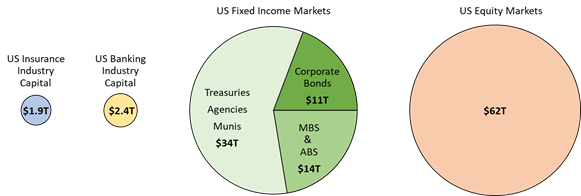

Many consumer financial transactions would fail as a result of geolocation-based fraud algorithms that rely on geographic spend patterns and/or device co-location at the point of transaction. Time stamps on financial markets transactions would soon become unreliable at the level of microseconds, which could trigger high-frequency trading algorithms to behave erratically and/or shut down, either of which could have an effect like the 2010 “Flash Crash”2.

But much like with the Y2K scare, it’s hard to comprehensively anticipate all of the devices and process which might have a GPS dependency. Many dependencies will be discovered only when something stops working.

The initial chaos would likely dissipate fairly quickly, as soon as workarounds and/or manual procedures were put in place of GPS-dependent processes. However, some sectors do not have feasible workarounds, or would be so frictionally impaired by workarounds, that impacts would persist as long as the GPS outage lasted.

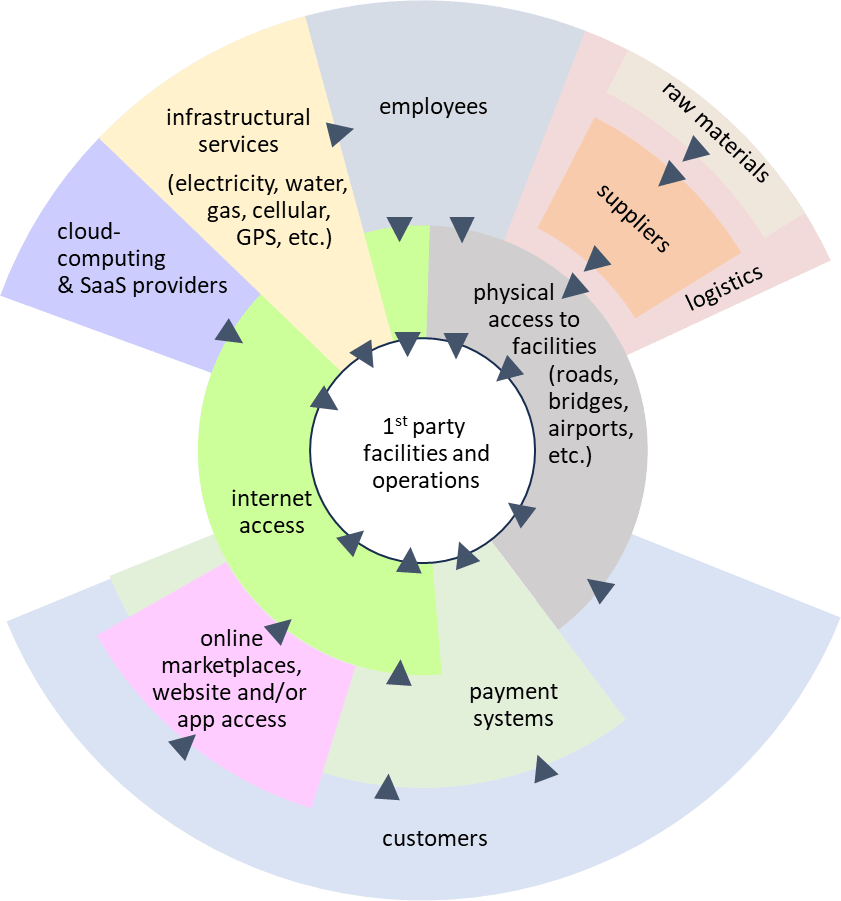

A 2019 study commissioned by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) estimates that a 30-day disruption to GPS could have $15.1 billion economic impact on the agricultural sector were it to occur at a critical time during planting season3, and an additional $30.3 billion of economic impact across all other sectors. Most of these economic impacts are indirect, frictional losses. Outside of agriculture, the maritime sector has the largest estimated impact, primarily driven by delays in port operations.

The NIST study’s economic impact estimate of $2.9 billion for location-based services in a 30-day GPS outage probably underestimates direct losses to businesses operating through mobile apps dependent on location-based services (which have in any case grown considerably since the 2019 date of the study). The easiest of these to understand are ride-share and delivery businesses: location and driving directions are at the core of their business model, and without GPS they would cease to function usefully. The four large publicly-traded companies in this sector – Uber4, Lyft, DoorDash and Instacart – combined have nearly $70 billion revenues and $30 billion operating profit per year. Adding in privately-held peers (e.g. GrubHub), self-driving taxis (e.g. Waymo, Zoox, Tesla), and shared scooters and bikes, the rideshare and delivery app sector is well over $200 million revenues per day and around $100 million operating profit per day.

Beyond rideshare and delivery apps, there are other apps where location is not core to the business model but is still a necessary ingredient. For example, online dating apps need to match users to other users in their area; Match and Bumble combined have about $4.5 billion revenues and $3.2 billion operating profit per year. Online gambling apps are required to verify the user’s location for compliance with laws that vary from state to state; FanDuel and DraftKings combined have about $20 billion revenues and $9 billion operating profit per year, account for about three-quarters of the industry. Comprehensively enumerating all of these location-dependent apps is quite challenging, but just between online dating and online gambling businesses, the tally is already over half the size of the rideshare and delivery app market.

A GPS outage would be very problematic for Pokemon Go.

Additionally, location-based mobile advertising would not function without GPS on the device. Apps that enjoy a higher likelihood of user acceptance of device location access – social media such as Instagram and TikTok, review apps like Yelp, weather apps such as The Weather Channel, etc. – could experience a loss of revenue as their advertisement inventory is sold into standard mobile ad campaigns rather than geo-targeted programs at higher prices. By some estimates, location-based mobile advertising spend is around $40 billion annually – or $110 million per day – but there is no straightforward way to estimate how much of that is premium over standard mobile ads.

Rideshare and delivery apps as well as location-based advertisers would be hard-pressed to find a workaround to not having GPS signals. Other apps might be able to adapt to less precise methods (e.g. IP addresses, cell tower triangulation, etc.) but making those changes and deploying updated apps to users would not be quick.

At somewhere in the ballpark of $200 million per day direct profit impact to businesses dependent on mobile device location services, the NIST study’s estimated $2.9 billion overall economic impact for location-based services in a 30-day GPS outage seems very low.

GPS Vulnerabilities

From a dependent user perspective, it doesn’t really matter why a GPS outage has occurred, only how long it lasts; the business impact is the same regardless of the cause. But it is worth considering some potential causes in order to roughly gauge both the likelihood and potential duration of a GPS outage. Following are some potential GPS disruption scenarios:

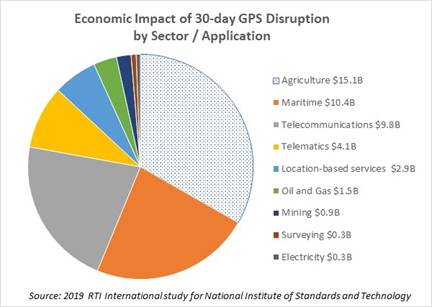

Geomagnetic storm

Large solar flares erupting from the Sun can launch a burst of charged particles towards the Earth that interact with Earth’s magnetosphere. On the one hand, this can result in a spectacular aurora visible at much lower latitudes than typical. On the other hand, the fluctuations in magnetic field and charged particles in the ionosphere can wreak havoc with power and communications on Earth. The noise in the ionosphere can distort and overwhelm the weak low-frequency GPS signal to the point where GPS receivers may read them inaccurately or may not be able to read them at all. In a strong geomagnetic storm, these effects can last for days with regional or global scale.

The GPS satellites are also vulnerable in a geomagnetic storm. Charged particles hitting the satellites can cause unexpected behavior in circuitry, including altering solid-state memory containing parameters or instructions critical to satellite operation. Low Earth Orbit satellites such as the GPS satellites may also experience drag, altering their orbits. The GPS system relies on accurate data for the satellites’ positions in orbit. Uncorrected orbits could lead to inaccurate GPS measurements, and eventually a risk of de-orbiting. A geomagnetic storm may also affect power and communications for components of the ground-based “Control Segment” which synchronizes the GPS satellite clocks, updates their position information, and manages their orbit corrections.

NASA’s Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) classifies geomagnetic storms on a 5-point scale, somewhat like hurricanes. According to this scale, in a G5 geomagnetic storm, which SWPC rates at about 1-in-3 annual frequency (4 per 11-year cycle), “satellite navigation may be degraded for days”.

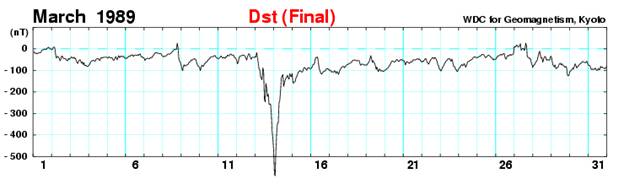

The March 1989 geomagnetic storm is the largest in modern record history, affecting power grids in North America (Quebec in particular) and interrupting control and communications with some satellites. The GPS system was not yet fully operational or open to civilian use, so we have no report of whether or not there was any disruption. It would have been a G5 on SWPC’s scale, and it had a peak Disturbance Storm-Time (Dst) index reading of -589 nanoteslas (nT)5.

The most recent G5 solar storm was the May 2024 “Gannon” storm6, which had a peak Dst reading of -412nT, not quite as severe as the 1989 event. The storm degraded GPS accuracy for self-driving tractors in the US Midwest for at least 4 hours on May 10th, 2025 – peak planting season for corn in particular – with lingering effects over the following two days. One study estimated that this could have resulted in up to $1.7 billion economic losses due to delaying a portion of planting into a less productive period a couple of weeks later.

The 1859 Carrington Event obviously pre-dates both precise measurement and SWPC classification but is estimated to have had a Dst of -900nt, far more severe than either the 1989 or 2024 events – a “G6” on a scale of G1 to G5. A Carrington-magnitude event would pose a potential threat to the GPS satellites themselves, which depending on the nature of impact and number of affected satellites could cause intermittent regional outages and accuracy degradation until satellites were corrected or replaced… some mitigations might be possible over an intermediate horizon, but it might take years to fully correct. Even if GPS satellites themselves were completely unaffected, it could result in multiple days of GPS signal disruption at a global scale.

NASA characterizes the Carrington Event as having about 1-in-500 year frequency, but it’s obviously somewhat uncertain given the relatively brief window of historical measurements, and estimates from academic studies are all over the place7.

Jamming and Spoofing

Deliberate disruption of GPS signals has become a commonplace tool in recent conflicts. Jamming refers to a noisy signal broadcast in the same frequency range as the GPS signal such that the GPS signal cannot be discerned by the receiver. Spoofing provides false GPS signals that cause the receiver to calculate a GPS position different than the actual position.

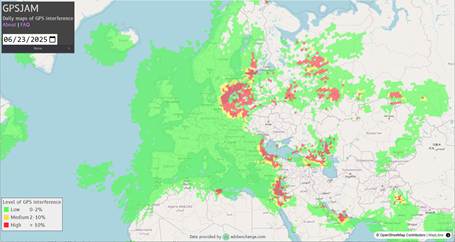

Jamming and spoofing can have legitimate defensive purpose, such as spoofing by the Israel Defense Force along their northern border to thwart Hezbollah rocket attacks. There is a wide zone of GPS disruption around Ukraine as both sides attempt to disrupt drone attacks.

Jamming and spoofing have other nefarious uses by pirates, terrorists and potentially state actors engaged in non-combat provocation or sabotage. There have also been instances of GPS jamming by commercial drivers attempting to circumvent their employer’s GPS-based fleet tracking systems.

To date, GPS jamming and spoofing incidents have generally been too localized – at most regional in the vicinity of combat zones – to pose a significant Systemic Dependency Risk threat. And the source of the attack can eventually be traced, so any widespread jamming or spoofing attack with meaningful economic impact would likely be eliminated fairly quickly. That said, there is a hypothetical risk of jamming or spoofing from satellite-based sources which could be more challenging to eliminate.

Satellite damage or malfunction

Space is an unforgiving environment, with hazards ranging from space debris to radiation to temperature extremes. Like most satellites, GPS satellites are made up of many components – solar panels, antennae, radio transmitters, atomic clocks, etc. — and the failure of any of those components could render a given GPS satellite unable to perform its essential functions.

The good news is that the GPS satellites are spread out in a Medium Earth Orbit almost 11 thousand miles above the Earth. That puts them out of harm’s way from the much more crowded Low Earth Orbit where you might worry about a Kessler Syndrome cascade of collisions and/or space debris creating even more space debris and more collisions such that multiple satellites would be at risk. While MEO is not without physical hazards – for example, a 2021 instance of a European GNSS Galileo satellite maneuvering to avoid collision with space junk – any such event in MEO would be unlikely to disable more than one GPS satellite, and we have several spares in orbit.

The bad news is that the GPS satellites have many design features in common, particularly within each batch (or “block”) designed, built and launched under a given contract. Unanticipated satellite design failures – for example, growing “tin whiskers” in space – can shorten the lifespan of whole classes of satellites with that design feature. And unfortunately, those unanticipated design failures only emerge after the satellites have been deployed for some time.

The challenge for the GPS satellites is that 12 of the 31 currently operational are from a single design class – “Block IIR” and “Block IIRM” – that have been in orbit between 16 and 28 years, against a design life of 10 years. The good news is that these satellites are “well seasoned” in the sense that any serious flaws probably would have emerged already, and most military and civil satellites last well beyond their design life. The bad news is that if any of these satellites’ components begin to experience high failure rates this far beyond design life, the entire batch of 12 may be subject to those high failure rates9. And the further bad news is that it takes years to replace them: the newest batch – “Block IIIF” – is not set to launch until 2027 at the earliest, at a rate of approximately 3 per year.

In the event of a malfunction impacting multiple GPS satellites, the first few failures would be managed by spare capacity with 31 operational satellites plus 2 in-orbit spares vs. the required 24 satellites for fully operational GPS. But if more than 9 are lost before replacement there would be an ongoing degradation involving lower accuracy and/or intermittency, potentially lasting for years.

Software risk

The GPS system’s “Control Segment” runs software algorithms that receive GPS satellite data from monitoring stations and produce instructions for the GPS satellites to synchronize their clocks, update their orbit data, and adjust their orbits when necessary. Like any software, it is subject to the risks of both programming errors and user errors, as well as malicious attacks.

On January 26, 2016, a software bug pushed out in conjunction with decommissioning one of the GPS satellites caused a “UTC offset anomaly” on 15 of the GPS satellites that lasted for approximately 12 hours. The time broadcast by the GPS satellites was only off by 13 microseconds, but that’s actually a huge problem both for location accuracy – approximately 4 kilometers given the location calculation’s sensitivity of approximately 0.3 meters per nanosecond – and synchronized timing applications.

It’s worth noting that the existing Control Segment system went operational in 2007. The “Next Generation Operational Control System” (OCX) project designed to replace the existing Control Segment system has run considerably behind schedule and over-budget relative to initial plans to deliver in conjunction with the launch of third-generation “Block III” GPS Satellites which began in 201810.

OCX was finally delivered in July 2025, and could go operational by the end of the year. The good news is that it will include features to improve GPS accuracy and robustness as well as enhanced cybersecurity protection. The bad news is that transition and early days of operation for system upgrades are often at higher risk for errors and malfunctions.

Control Segment risks have the unhappy characteristic of potentially applying to many or all of the GPS satellites simultaneously, creating the potential for a disruption on a global scale.

The good news is that any errors are quite rapidly detected by GPS users, including sophisticated quality checks for sensitive time-based applications. GPS satellites with bad signals can easily be marked “unhealthy” so that user applications can ignore them, at the cost of potential degradation of service if too many are unhealthy. Errors in the nature of bad data sent by the Control Segment to the GPS satellites can be corrected. The bad news would be any erroneous GPS satellite position instructions, which might take more time to correct or in the worst case be irreversible.

Users’ GPS receivers may also be subject to systemic software issues, such as the “GPS Week Number Rollover” problem on April 6, 2019 requiring software or firmware patches for devices unable to accommodate the rollover event.

…so, the GPS system clearly has multiple vectors of vulnerability. For most of these vulnerabilities, the geographic scope and duration of disruption would likely be relatively local and brief. However, with some lower but non-zero probability, each of these vulnerabilities is capable of regional or global scope, partial to full degradation of services, and prolonged duration in the range of days to years.

You Are Here. So now where do we go, and how do we get there?

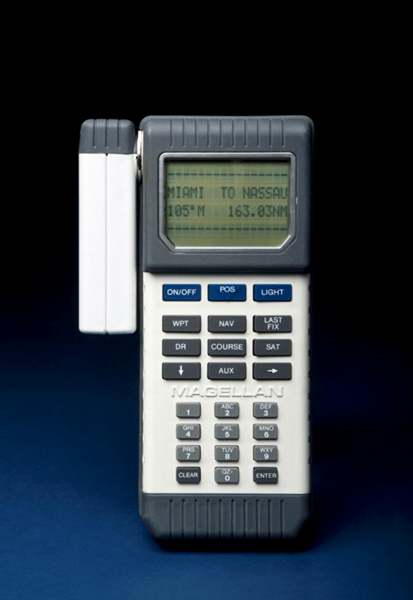

GPS disruption risk illustrates many of the key features of Systemic Dependency Risk in general. It is a widely-shared dependency on a single point of failure with multiple vulnerabilities, and that dependency is a relatively new phenomenon as a result of the new-ish technology itself in combination with the business models that have grown around it. Traditional insurance will not cover the risk of GPS disruption (other than a plane or ship accident), and the risk of accumulation across policies combined with lack of ratable history leaves it stuck squarely in the commercial insurance “protection gap”.

So what are companies exposed to this risk to do? The primary mitigation is to develop a “run book” so that workarounds can be put in place as swiftly and frictionlessly as possible. This is obviously a requirement and generally already in place for applications where safety of lives is at risk, such as aviation. Where commercial interests rather than lives are at stake, even a suboptimal workaround with higher costs or lower revenue generating capacity is better than complete outage and/or chaos. Ideally, redundancy might be a better mitigation, but the scale of GPS systems is such that it likely out of reach for any individual company.

The government is aware of the risk of GPS disruption and while some improvements are in progress or planned, they have been budget-constrained and/or not able to act with speed commensurate to urgency. Similar to other public infrastructure risks, without any commercial forces to counteract insufficiently robust service, it’s easy for government to prioritize more politically salient spending with near-term tangible impact over long-term investments to reduce the risk of improbable events (unless and until the improbable happens, in which case there will surely be plenty of finger-pointing, and possibly also the political will to invest in solutions). Because GPS is free, there is little incentive to create a private sector alternative. This seems like an opportunity for private-public partnerships, particularly for local non-satellite navigation signals and clock synchronization.

As with many Systemic Dependency Risks, a capital markets-backed insurance solution with a parametric trigger offers some potential future hope. But even with such a solution, and more importantly in the absence of any insurance solution, companies need to “self-underwrite”: identify where GPS disruption risk might affect their business, estimate the frequency and severity of potential GPS disruption scenarios, and assess the potential magnitude of losses in those scenarios in order to put a “cost of risk” against GPS disruption. Recognizing the cost is the first step to prioritize doing something about it.

- GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) is the generic term, while GPS (Global Positioning System) is the specific version created by the US government. Europe’s Galileo is similar technology but more recently operational (2016). There is also Russia’s GLONASS and some regional networks as well as non-satellite alternatives. ↩︎

- This whitepaper speculates that GPS signal spoofing could trigger such an event, citing research that has even suggested that the 2010 Flash Crash was triggered by time stamp errors. ↩︎

- For context, see below discussion of potentially up to $1.7 billion economic impact on corn farming due to GPS disruption from May 10, 2024 “Gannon” solar storm. ↩︎

- The risk factor section of Uber’s 10-K filing explicitly calls out third party dependencies including GPS. Bird – prior to its 2023 bankruptcy and reconstitution as a private company – had a very blunt assessment of GPS dependency in its 2022 10-K risk factor disclosure:

“Our service relies on GPS and other Global Satellite Navigation Systems (“GNSS”).

GPS is a satellite-based navigation and positioning system consisting of a constellation of orbiting satellites. The satellites and their ground control and monitoring stations are maintained and operated by the U.S. Department of Defense, which does not currently charge users for access to the satellite signals. These satellites and their ground support systems are complex electronic systems subject to electronic and mechanical failures and possible sabotage. The satellites were originally designed to have lives of 7.5 years and are subject to damage by the hostile space environment in which they operate. However, of the current deployment of satellites in place, some have been operating for more than 20 years.

To repair damaged or malfunctioning satellites is currently not economically feasible. If a significant number of satellites were to become inoperable, there could be a substantial delay before they are replaced with new satellites. A reduction in the number of operating satellites may impair the current utility of the GPS system and the growth of current and additional market opportunities. GPS satellites and ground control segments are being modernized. GPS modernization software updates can cause problems with GPS functionality. We depend on public access to open technical specifications in advance of GPS updates.” ↩︎ - Dst measures changes in the Earth’s ring current. It is calibrated to a normal value of zero, and large negative values indicate a strong solar storm. ↩︎

- Another Systemic Dependency Risk event in 2024! The “Harvey-Irma-Maria” year for Systemic Dependency Risk: Change Healthcare ransomware attack, Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse, CDK Global ransomware attack, and CrowdStrike outage. ↩︎

- A widely-cited 2012 study estimated the frequency at 12% per decade, about 1-in-80 years. However, a more recent 2019 study gives a 95% confidence interval from 0.46% to 1.88% per decade, or about 1-in-2000 to 1-in-500 years, while another recent 2020 study estimates 0.7% annual frequency, or about 1-in-150 years. ↩︎

- GPSJAM data are derived from aircraft GPS receivers registering “low accuracy”. Blank areas have insufficient air traffic reporting, e.g. due to closed airspace. It’s likely that GPS signal jamming has been widespread throughout the blank area in and around Ukraine. ↩︎

- It’s also worth noting that the 11 operational GPS satellites in “Block IIF” launched between 2010 and 2016 are near or beyond their 12 year design life; one of the original 12 “Block IIF” satellites experienced a clock failure 2 years into its life and is non-operational. ↩︎

- The legacy Control Segment was upgraded and an initial phase – “Block 0” – of OCX in 2017 to accommodate launch and control of “Block III” satellites as well as a subset of their new capabilities. ↩︎